LC 00478: verschil tussen versies

Geen bewerkingssamenvatting |

Geen bewerkingssamenvatting |

||

| Regel 8: | Regel 8: | ||

[[Bestand:Index cards.png|gecentreerd|miniatuur|'''Figure:''' example of a CRC card.]] | [[Bestand:Index cards.png|gecentreerd|miniatuur|'''Figure:''' example of a CRC card.]] | ||

CRC cards are used in an interactive session with stakeholders. The goal is define classes and add responsibilities and collaborations to them during the session. The card’s limited size matters because it blocks off adding too much unnecessary details on the cards at this stage. The big picture should not get out of sight in a session. After an initial set of classes has been established and written down on CRC cards, one class per card, the cards are divided amongst the stakeholders. This marks the beginning of designing the system interactively. Scenarios are typically used for this purpose. For instance, a customer purchases a good from a company. Which class is responsible for handling the request, and which other classes should be involved, and so on? The stakeholders write down classes’ responsibilities and collaborations on the cards they held responsible for. If all went well, the scenario can be acted out afterwards by the stakeholders acting their parts, i.e., acting according to the responsibilities written down on their CRC cards, including passing on requests to collaborators. | CRC cards are used in an interactive session with stakeholders. The goal is define classes and add responsibilities and collaborations to them during the session. The card’s limited size matters because it blocks off adding too much unnecessary details on the cards at this stage. The big picture should not get out of sight in a session. After an initial set of classes has been established and written down on CRC cards, one class per card, the cards are divided amongst the stakeholders. This marks the beginning of designing the system interactively. Scenarios are typically used for this purpose. For instance, a customer purchases a good from a company. Which class is responsible for handling the request, and which other classes should be involved, and so on? The stakeholders write down classes’ responsibilities and collaborations on the cards they held responsible for. If all went well, the scenario can be acted out afterwards by the stakeholders acting their parts, i.e., acting according to the responsibilities written down on their CRC cards, including passing on requests to collaborators. | ||

{{LC Book config}} | {{LC Book config}} | ||

| Regel 22: | Regel 25: | ||

|Show VE button=Ja | |Show VE button=Ja | ||

|Show title=Ja | |Show title=Ja | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{LC Book additional | {{LC Book additional | ||

|Preparatory reading=LC 00479 | |Preparatory reading=LC 00479 | ||

|Continue reading=LC 00481 | |Continue reading=LC 00481 | ||

}} | }} | ||

Versie van 30 nov 2020 12:28

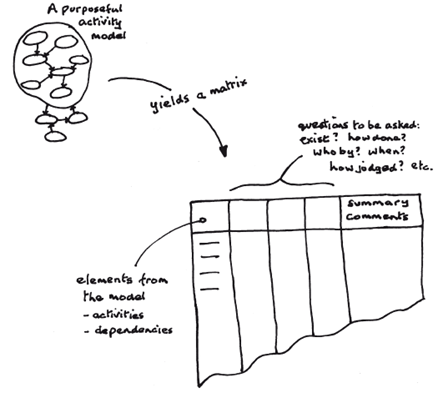

Once the worldviews have been established in the form of Purposeful Activity Models (PAM), a structured dialog between the stakeholders, e.g., the CATWOE’s customers, actors, and owner, can be conducted. As discussed before, a PAM is a notional construct, which means that the activities modeled in a PAM do not necessarily occur in reality. They reflect how things ought to be done in the context of a worldview. The purpose of a structured dialog is accommodation of worldviews to find consent in adapted ways of doing things that are actually going to be realized.

Again, SSM as a methodology does not prescribe how to conduct a structured dialog, although some techniques have been developed and put in practice. The easiest way, but certainly not the most thorough way, is to conduct the dialog informally. A more structured approach is by using a chart matrix to capture the answers to probing questions like: here is an activity in this model; does it exist in the real situation? Who does it? How? When? Who else could do it? How else could it be done?

Another technique, stemming from object-oriented software development practices, are CRC cards (cite{}). It is a technique for analyzing and designing information systems based on Object-Oriented (OO) principles. Such systems are made up by objects (for example, customers, inventories, and departments) that collaborate with other objects to fulfill their tasks. This corresponds to the systems thinking idea of composing a system (i.e., the information system) out of sub-systems (i.e., the objects).

In OO jargon, an object is an instance of a class, which means that a class can be seen as a kind of abstract entity, i.e., a type or a category, that describes common characteristics of objects that belong to the same class. For instance, objects like Shell, Philips, and KLM are all instances of the class Company. The responsibilities and collaborations of a class are summarized on CRC cards. These are index cards having the standard 3 by 5 inches (76.2 by 127.0 mm) size. (Index cards are hopelessly out of fashion, but easy to recreate if you cannot buy them in your local stationary shop anymore.)

CRC cards are used in an interactive session with stakeholders. The goal is define classes and add responsibilities and collaborations to them during the session. The card’s limited size matters because it blocks off adding too much unnecessary details on the cards at this stage. The big picture should not get out of sight in a session. After an initial set of classes has been established and written down on CRC cards, one class per card, the cards are divided amongst the stakeholders. This marks the beginning of designing the system interactively. Scenarios are typically used for this purpose. For instance, a customer purchases a good from a company. Which class is responsible for handling the request, and which other classes should be involved, and so on? The stakeholders write down classes’ responsibilities and collaborations on the cards they held responsible for. If all went well, the scenario can be acted out afterwards by the stakeholders acting their parts, i.e., acting according to the responsibilities written down on their CRC cards, including passing on requests to collaborators.